A special post this Thanksgiving evening from Bruce Orser and Elizabeth Curler:

“Green Mountain Morgan’s Last Hurrah”

Research done by Bruce Orser; written by Elizabeth Curler

Over the span of his lifetime, Green Mountain Morgan 42 (ca. 1834-1863) fostered a reputation as the preeminent epitome of a military parade horse. He was continually compared to the war horse of Job by various writers. One writer proclaimed Green Mountain was the “animal that, of all horses we ever saw, most nearly answers the description of Job’s warhorse, ” whose “neck was clothed with thunder.”

The Vermont Phoenix reminded his admirers that New York Governor William H. Seward (1801-1872), at the 1852 Vermont State Fair, stated “that neither in this country nor in Europe had he ever beheld a horse of such magnificent action as a parade horse.” He is known to have served as a parade horse in Vermont, New Hampshire, Massachusetts, and New York. When owned by Silas Hale, of South Royalston, Massachusetts, he was in demand for 60-100 miles around.

What was demanded of a popular military parade horse? Green Mountain was the fourth generation of stallions that possessed the qualities desired: “great” style, action and spirit. In addition, endurance was necessary as they were expected to keep this up all day. For the annual militia trainings this would be for one day, but musters often lasted at least two days. Green Mountain knew the routine so well that “on one occasion the commanding officer, the better to show Green Mountain off, took off his bridle and rode the horse in his evolutions for fully one-half hour in the general and regular parade.”

In addition to being a renowned parade horse, “Old Green Mountain Morgan” was a popular sire. In 1855, he was sold to a company in Williamstown, Vermont by Silas Hale of South Royalston, Massachusetts and was kept by Milton Martin for several years at stud. Vermont abolished its militia in 1844, so his tenure as a parade horse was believed to have ended. However, he was not forgotten.

When Green Mountain was a reported 25 years of age in 1859, he was engaged for the use of Governor Nathaniel Banks (1816-1894) of Massachusetts. There was to be an “old-fashioned” encampment of the Massachusetts militia held in Concord, MA in September of that year. Green Mountain was to serve as Banks’ mount during the event for the sum of $45.00 (in today’s dollars equivalent to $1,100) and expenses.

This newsworthy bit was noted in several newspapers of the day. The Constitution, published in Washington, DC, commented that Governor Banks would not have to display “much agility and equestrian skill” to ride a “perfectly trained parade horse” that was “thirty years old.” The New York Tribune joined in stating that ” the idea of a statesman who possesses all his power in a state of such vigor and discipline that he is able to mount and control a stallion is something startling.” It was noted that “the old fogy school of public men got on horseback” only under compulsion and then, generally, on a “shambling old mare ” or a broken down gelding. That a public figure would choose to ride a stallion was considered astonishing.

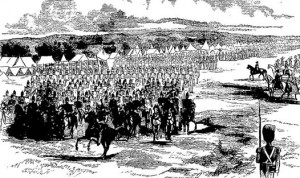

The Massachusetts militia encampment was expected to attract large crowds of spectators. In anticipation of this, the Fitchburg Railroad contributed $2,000 toward the expenses of the encampment. In addition, they provided free passes for the estimated 6,000 soldiers that would participate. They believed that the spectators attending the event would more than recoup the expense (an estimated 50,000 attended).

When the time came for Green Mountain to be shipped to Massachusetts for the event, both Martin boys. Fred and Albert, accompanied him. When Banks mounted Green Mountain, he promptly dug in his spurs. According to Ruth Martin Curtiss (b. 1898), great-granddaughter of Milton Martin, just as promptly Banks was thrown by the venerable old parade horse. Fred Martin then mounted the horse and rode him to settle him. No mention of this embarrassing (for Banks) episode is mentioned in any news accounts.

The first day consisted of a march through Concord, Massachusetts, to the ‘monument,” then on to the Revolutionary War battleground, and finally back to the camp. The second day involved field operations, which entailed maneuvers and firing of weapons. The third day consisted of the Grand Review.

Banks apparently did ride the horse eventually as it was reported that the “general feeling” among the spectators was that “instead of the horse being honored by bearing in the cavalcade the distinguished Governor of Massachusetts, His Excellency was rather honored in being allowed to bestride the finest parade horse in the country.” D.C. Linsley wrote: “We feared that age must have dimmed the fire of his eye, checked the full and vigorous pulsations of his blood and tamed the unflinching courage and dauntless bearing which have never yet failed to rouse the enthusiastic applause of all beholders. The stanch old veteran was the ‘observed of all observers.'”

General John Wool, who made his mark during the Mexican War, was present at the encampment and proclaimed Green Mountain to be the “finest parade horse ever.” This was the last major public event in which Green Mountain is known to have participated. In spite of his age at the time, he made his presence known.